The Sept-Îles Blueprint: How Canada Built Big, and Can Do It Again

The story of the resource and energy developments that shaped modern Northeastern Quebec and Labrador

This past June, my wife’s work took us to the Innu village of Nutashkuan, a trip that involved a long drive along Quebec’s scenic Route 138. For over 1,000 kilometers, the road winds through beautiful, largely untouched boreal forest and coastal nature.

That scenery changed abruptly when, after cresting a hill, we were met with a bay packed with cargo ships and a web of transmission lines. We had arrived in the port city of Sept-Îles.

That fascination sent me down a historical rabbit hole, uncovering a story of ambition, energy, and industrial might. This is that story.

Iron Ore Company of Canada (IOC)

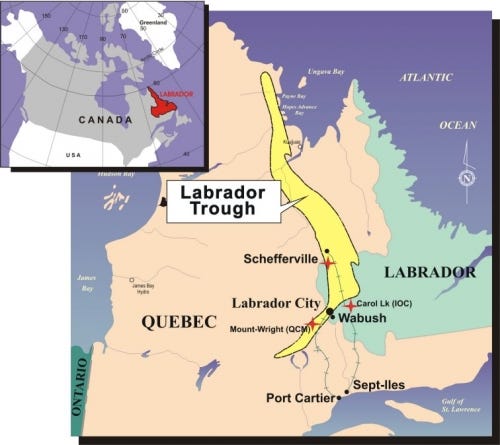

This story begins with the discovery of vast iron ore deposits in a region called the Labrador Trough, a massive geological formation straddling the Quebec-Labrador border. Although these deposits were discovered in the 1890s, their development was long delayed by the region's remoteness.

The turning point came after World War II, as the high-grade iron ore deposits in the American Midwest's Mesabi Range began to deplete. Facing a future shortage, a consortium of American steel companies formed the Iron Ore Company of Canada in 1949 with the express purpose of developing these vast northern resources.

Quebec North Shore and Labrador Railway (QNS&L)

To get the ore from the remote inland mines to a deep-water port, IOC had to build a lifeline. The result was the Quebec North Shore and Labrador Railway (QNS&L), a 578-kilometer line connecting the new town of Schefferville to Sept-Îles. Constructed between 1950 and 1954, it was considered a modern engineering marvel, as workers battled an extreme climate and blasted through the rugged, solid rock of the Canadian Shield to complete it.

Sept-Îles

With the QNS&L railway established, the once-small town of Sept-Îles was set to explode. Chosen as the railway's southern terminus for its deep-water bay, the town was rapidly transformed by the Iron Ore Company of Canada. IOC built out the port, constructed processing and pelletizing plants, and laid down the city infrastructure needed to support the massive influx of workers.

The resulting boom was staggering. The population skyrocketed from just 2,000 inhabitants in 1951 to over 14,000 a decade later. Fueled by ore, the Port of Sept-Îles became an economic powerhouse, and by the late 1970s, it was the second-busiest port in all of Canada by tonnage, trailing only Vancouver.

Churchill Falls Generating Station

The region's massive industrial growth demanded an equally massive power source, leading Quebec and Newfoundland & Labrador to develop their vast hydrologic resources. The resulting magnum opus was the Churchill Falls Generating Station.

At the time, it was the largest and most ambitious civil engineering project in North America. The industrial ecosystem that had sprung up around the mines proved essential to its creation: the QNS&L railway transported supplies, and the nearby Twin Falls generating station (originally built for the IOC mines) powered the construction.

Upon completion, engineers decommissioned the Twin Falls station entirely, diverting its water flow into the Churchill Falls reservoir after determining this would generate three times more electricity. The new station went into full production in 1974, becoming the largest power plant in the country and one of the most powerful in the world.

Aluminum Alouette

The late 1970s was a period of abundance for the region. Iron ore was mined and shipped down to Sept-Îles, powered by Churchill Falls and other hydroelectric power stations. Quebec continued to harness its hydrological resources, making electricity plentiful for the Province and its neighbors.

The 1980s, however, brought a global recession that saw demand for iron ore plummet. This created severe economic hardship for a region almost solely dependent on the commodity, and the population of Sept-Îles, which had peaked at 31,000 in 1981, began to decline. The crisis forced the Quebec government to make a strategic pivot. With demand for iron ore collapsing, it turned to the region's other great asset (its vast and affordable supply of hydroelectric power) to attract a new industry: aluminum smelting.

In 1987, the government's investment arm, the Société générale de financement (SGF), took the lead in assembling an international consortium to build a new, world-class smelter. Two years later, the creation of Aluminerie Alouette was announced. The chosen location was Pointe-Noire, across the bay from Sept-Îles. The site was ideal, offering direct access to the deep-water port, a ready supply of skilled industrial labour, and proximity to Hydro-Québec's Arnaud substation—a key node on the grid carrying power from Churchill Falls.

Today, Aluminerie Alouette is the largest aluminum smelter in the Americas, capable of producing 630,000 tonnes of primary aluminum per year.

Takeaways

The story of Sept-Îles is more than a regional history; it is a blueprint. It stands as powerful proof that when Canada commits to harnessing its resources, it can execute massive, world-class infrastructure projects with astonishing speed and ambition. From an iron ore mine connected by a rugged railway, to one of the world's largest hydroelectric stations, to a globally significant aluminum smelter, the region is a living monument to an era of industrial might.

But this history is not a museum piece. It offers a clear and relevant playbook for the challenges Canada faces today. So, what can we learn from the industrial symphony that created modern Sept-Îles?

First, it provides a model for strategic public-private partnership. The Aluminerie Alouette project is the perfect example: a government entity acted as the catalyst, assembling an international consortium of private partners to build a mega-project that revitalized an entire region. This is a blueprint for leveraging private capital and expertise to achieve public goals.

Second, it demonstrates the power of building on existing infrastructure. The QNS&L railway, built for iron, was used to construct Churchill Falls. The power from Churchill Falls was then essential for the Alouette smelter. Canada does not need to start from scratch; it has established corridors with aging infrastructure (transmission lines, railways, roads, and ports) that are ripe for upgrades to boost national productivity.

Finally, and most critically, the story teaches us how to build better this time. We must learn from the past by ensuring that all stakeholders, especially First Nations communities, are partners from the beginning. A stark contrast exists between the top-down approach of the Churchill Falls project, which had devastating impacts on the Innu Nation, and the more collaborative (though imperfect) model of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. With modern commitments to streamline environmental assessments and a deeper understanding of true partnership, we can avoid the mistakes of the past.

These lessons arrive at a pivotal moment. Many believe we are on the cusp of a new age of abundance, driven by the twin revolutions of artificial intelligence and electrification. This technological push, combined with a societal hunger for opportunity and shared purpose, is creating an alignment among leaders that we have not seen in decades. The ambition that carved a railway through the Canadian Shield and built the largest smelter in the Americas is not a relic of the past. It is a national capacity that lies waiting to be unleashed once more.

I used Gemini 2.5 pro as my research and editing assistant.

Mentioning Churchill Falls without discussing how unfair it was for the province of Newfoundland AND Labrador is strange as it is a textbook example of the problems besetting the Canadian economy vis a vis federal powers and interprovincial trade. As with respect to private-public partnerships, the extant research raises a myriad of concerns about the model, not the least of which is the cost of capital in an age of low interest rates.

Industrial policy is an age-old problem in Canada that has challenged the brightest Canadians going back generations. In lieu of solving this conundrum, we could develop the most environmentally-sound methods to exploit our natural resources while simultaneously working on multilateral agreements to enforce high standards across the world.

This is an awesome story. Thank you for sharing.